Writing Trauma: How Hard Is It?

In a 2022 blog, my partner Marie Posthumus wrote:

“In my world, writing about difficult emotions and describing the trauma I’ve experienced is risky. I am more easily drawn to broadening my understanding by listening to the voices of those marginalized and those who have worked in the field of sexual trauma to alleviate the injustice and the suffering.

When I started this blog, I did not feel well and went to lie down. Then I made myself some tea and stared out the window before trying again.

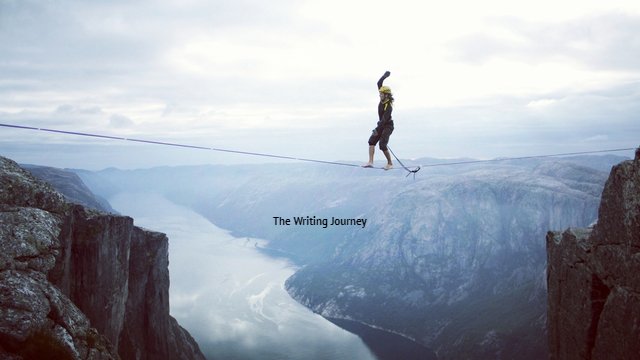

Writing my personal trauma is like an archaeological dig. I’m separate and alone. I dig down, bit by bit, and find some small thing, and then go deeper, and dig some more, removing layers, and revealing more. I very gently brush away the dust and debris. Take a breath, find some clarity, and with care lift the words up, into the light. Then began the analysis of artifacts and human activity with my pen.

Recently, I had the opportunity to read one of my stories to an audience in a literary salon. Writing the story was difficult and reading it out loud took determination and concentration. My mouth went dry, and I was visibly nervous. To say the least, it was very uncomfortable. But it was a triumph. People heard me. People understood me. They were moved- it had meaning. Now, the experience is real. And now, it is written down, outside of myself – dug out of my heart, dusted off, and on paper. An indescribable feeling.”

The Benefits of Writing About Trauma

The Psychosynthesis Trust Jun. 27, 2017

“Another possible reason why writing about trauma might be helpful is that it affords us the ability to reprocess our experience from a safe place, enabling us to experience a type of mastery and control over the trauma, and overcome the sense of helplessness.”

My partner Marie’s beautiful description is illustrative of gaining personal power. The kind of power that eases the burden of keeping quiet when you want to scream.

It wasn’t easy to write about my gang rape in high school. In fact, what I called The THING, was nicely packaged, and tucked away. When I walked into a writing class with the memory of all the journals I’d burned, I focused on writing a family history for my grandchildren announcing I wouldn’t write my story, just those of my ancestors.

As the class progressed, and as I dutifully did the homework, the nicely packaged, tucked away THING began to emerge. Like a monster, you don’t know what it’s thinking, or what will happen when it gets loose. You can’t gauge the danger to yourself or others because it is, after all, a monster.

I moved to my laptop and started to write stuff down….

I began to list, words, feelings, color, smell, light, and dark. “Wouldn’t it be nice to disappear…” are the words I used the morning after the party, that summer 56 years ago.

My words were choppy and disorganized—the words formed sentences then, formed into a list. I looked up poetry forms and found one where the words are repeated, stanza after stanza, like a mantra hummed to the tune of begging.

Drifting upward, never falling,

It might be nice to disappear,

Up to the sky above the trees.

Swirling mist with small thin fingers

And softly float among the stars.

God, move close to grant an answer.

The THING operated on me as a powerful energy source, affecting every breath I’d ever taken. I started to write. Then fast, the monster hit me from the outside. In reality, sound and images were just ahead of me on the TV screen.

As Christine Blasey Ford described her experience at a party in college. I was instantly there, tied up, my mouth covered. Taste and smell were as real as they were at the party; wallpaper designed as a wooded forest, metallic blood, throat squeezed, acrid sweat, and boys jeering laughter showing on the face of a man who would be a Supreme Court Justice. It acted like a brutal, vicious time machine.

In an interview with Dr. Cindy Childress, Marie and I asked her what trusted technique she used to stimulate writing about traumatic events.

“If it’s unspeakable or unsayable, you know it’s unreasonable to ask someone to magically write it down because they have a pen, paper, and a creative writing teacher. Any good writer’s process is to keep revealing, and when you pull back one layer, you find another….that is true of almost every writer.”

“Some things are forbidden, so you need to understand the “NO” voice that comes up. I believe it’s extremely important to take a minute to discover who’s in the driver’s seat.” -Childress

In Psychology Today, Art Markman, Ph.D. writes:

“Research by my colleague Jamie Pennebaker and his colleagues suggests that one of the best therapies for this kind of psychological trauma is also one of the simplest: writing.

People are asked to spend three consecutive days writing about one or more traumatic events.

The people doing the writing do not have to believe that anyone will ever read what they wrote.

Making these traumatic events more coherent makes memories of these events less likely to be repeatedly called to mind, and so they can be laid to rest.”

Now, I’ve written about the thing. It’s not in caps anymore. It lives, along with other traumas that struggled to be known, free from my mind, existing outside of me, on its own, in its place, in a book.

At Our Silent Voice, www.oursilentvoice.com, we say writing your story is a powerful start to building a foundation of strength to end the silence. All stories start ugly and rough with raw edges of random, messy words. Perhaps reading the stories and just starting the process of writing your story can cut through the fog of indecision.

In our book Our Silent Voice: End the Silence, our writer’s scream. They’ve gained strength in truth and combining their voices is freeing. If our book is for you, get it here. https://www.oursilentvoice.com/books

Submit your story for editing: https://www.oursilentvoice.com/submit

We’re Listening